Beyond AI

GPT Engineer – build an app with a SINGLE prompt! Tutorial

💡 This is the second part of the interview with Iwona Białynicka-Birula. Read the first interview here – click.

Previously, we discussed Iwona's life experiences. In this interview, we focus on what it is like to work with artificial intelligence in the USA.

Watch and listen to the full interview on YouTube:

You can also listen on podcast platforms:

[Ziemowit Buchalski]: And what were your experiences at Facebook, since you worked there too?

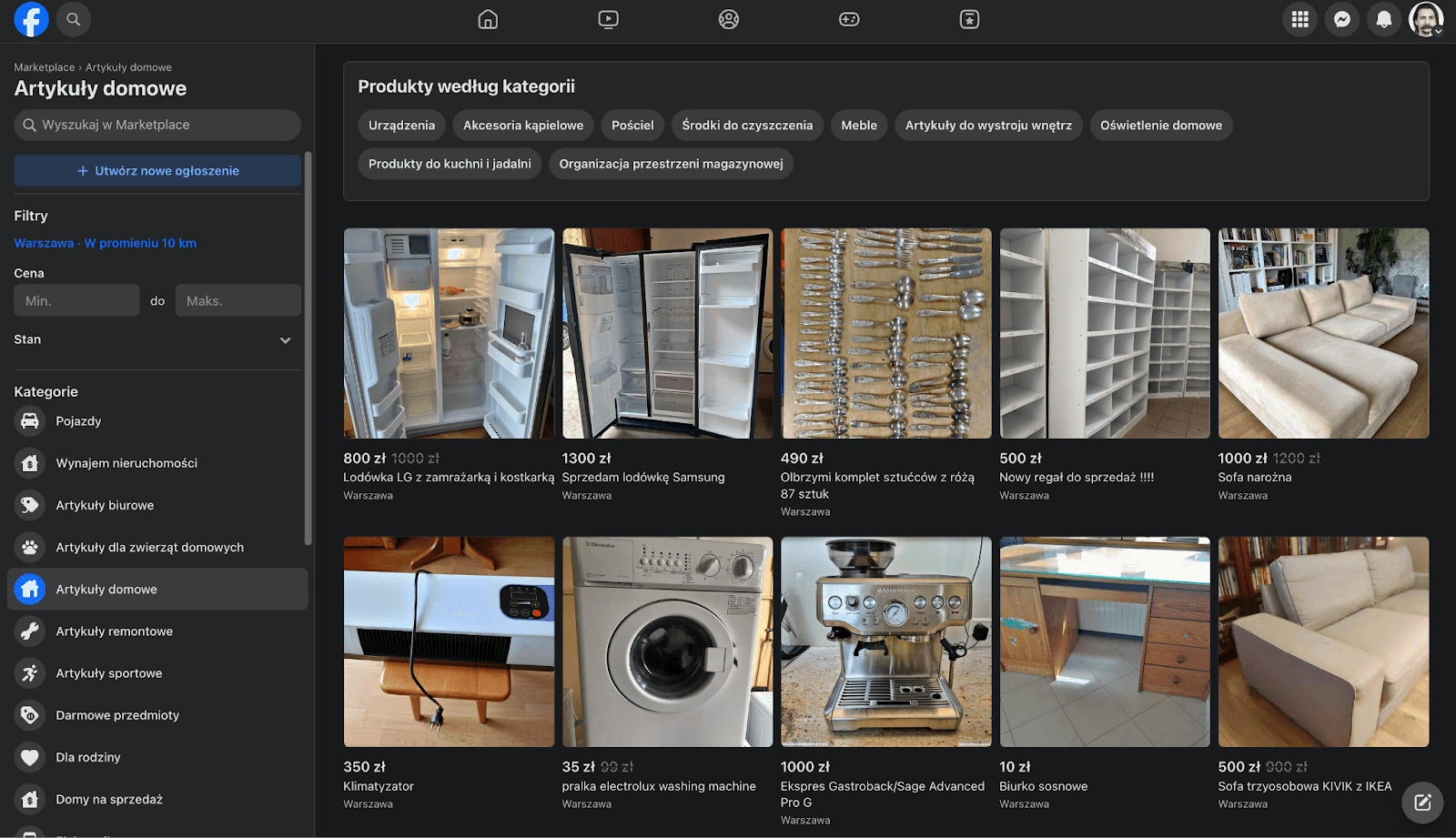

[Iwona Białynicka-Birula]: Yes, at Facebook, I worked mainly on Marketplace. Facebook Marketplace is a very popular product—I heard it is in Poland as well. My task was cataloging, essentially introducing structure to all those listings on Facebook Marketplace. Because, as is well known, a person posting an ad on Facebook Marketplace often doesn't provide any category, anything. They take a photo, write some description. Sometimes they just write: "For sale." It's very hard then to create a catalog of all these products and understand that these are similar products and those are not. So, I created a system there that automatically analyzed all these ads and organized them into a hierarchy with categories, subcategories, attributes, and so on.

Later, for a while, I dealt with video ranking, specifically music videos, which I don't think are available in Poland. You have to pay those recording companies. However, in the States, we had licenses to distribute those music videos. And we had to put them into all those feeds intelligently so they would interest people. We had to understand what kind of music taste someone had. And that was interesting because I learned a bit about how a newsfeed ranking algorithm works—it's quite controversial. Some people believe it even harms mental health.

You trained models to increase the viewership specifically of music. That was your defined task—artificial intelligence, but not generative, just deep learning.

Yes, that was before the boom of generative AI. I think a lot would have changed now as a result, because in Meta, there was a lot of... well, maybe not in ranking. In ranking, we had a lot of organic data because we knew who clicks on what and who likes what, so there was no shortage of data for doing supervised learning. However, in something like Marketplace, for example, it was very much lacking because we didn't have those products tagged with categories or attributes. Facebook employed masses, tens of thousands of people, who made such labels, mostly for moderation—meaning making sure someone didn't write something nasty or illegal. They watch those posts all day and tag them if there is terrorism, hate speech, or something like that. However, in Marketplace, we only had access to a small percentage—for example, 10,000 man-hours a week—and they tagged all those data for supervised learning. I think now at Meta—and the reason why Meta invests so much in their own models, LLaMA—is that they can probably replace much of that work with a model that will automatically label it and thus produce data for machine learning.

There is an episode on our channel, where, two months ago, I made a simple automation where, based on a single photo and thanks to the use of the GPT Vision model, it's possible to prepare sales content. You take a photo, the model detects what's in the photo, thinks of people for whom such a thing might have some value or meaning, and then thinks of what they could achieve with it and writes the ad content for that. So, it does much, much more than the task you were performing. However, that's probably a five-year difference in technology, and today such categorization is probably one line written in Python, and it would happen better or worse.

But regarding the scale—you mentioned that sometimes the work of tens of thousands of people was used to prepare data for models. But surely the organization of work in a project like Facebook must have been appropriately organized? Were there AB tests, or how did that happen? If you could tell us.

Yes, basically everything at Facebook, and later at Meta, happens based—even to an extreme—on so-called AB tests. This consists of testing every system feature using a controlled experiment. So, let's say we want to decide if a button should be blue or green; we divide our users randomly into two groups. One group gets the green button, one gets blue, and that experiment runs for, say, a week. Facebook has a lot of users, billions, so a lot of data can be collected in a short time. Then we compare those two populations: who spent more time on Facebook, who liked more, who clicked more, who watched videos longer. All the data we care about. Then—and this is very important—we measure statistical significance, meaning to what extent we are convinced that the result we saw did not occur randomly. Because obviously, if the population is small, someone might just happen to watch more by chance, and that could affect the difference. However, with large numbers, the probability that what we observe happened accidentally decreases, and we gain more confidence that the result is truly caused by that difference in button color.

In the case of your projects and the changes you made, how large were those samples and the populations being tested?

Well, it depends, because Facebook Marketplace itself, for example, is available in many countries, but often we focus on a subset of the population, and even then, there were always so many users. However, in the largest amount, it's actually that 1 billion or 3 billion—depends on how you count—Facebook users that you can experiment on.

It should also be mentioned that a career at Facebook is directly dependent on the results of these tests. Meaning, every six months there is a performance review; you have to show that you launched some tests, and the features you proposed had such and such an impact. Without that, you can't even remain employed at the company. This obviously has its advantages, because it means everything must be measurable and you must approach things systematically and not make decisions randomly. However, the downside is that not everything can be measured—specifically, longer-term effects like brand recognition or how reliable Facebook is as a source of interesting videos are very hard to measure. This isn't something that can be measured in a week, and consequently, changes whose effect couldn't be measured were not introduced. That, unfortunately, frustrated me very much there.

And the fact that every six months you face such a heavy verification point—whether you'll still be working or not—all depending on the result of your work. Wasn't that stressful?

Well, at Meta, it was less stressful than at Google, for example, solely because the managers were much better trained. A manager would say at the very beginning of the half-year what the expectations were, and you just had to meet them. There was no surprise when the half-year ended because you knew what needed to be done. It was a bit frustrating if what needed to be done wasn't actually in the company's best interest, but you knew you had to do it to get the performance review. In Google, for example, there isn't such respect for managers, especially in some organizations, and then people who are just very good at programming become managers, but they don't know what needs to be done—that they need to sit down like that with their employee at the beginning. Consequently, there it was literally a roulette. And that was more stressful.

Well, I think that's different from our Polish realities, where programmers simply get a task and are held accountable for completing the task, not necessarily for the business effects. Yes, because I understand that here the business effect mattered—for example, extending the time people spend watching videos. And your task was to make millions or billions of users spend more time on music videos.

Yes. Both Google and Meta are so-called "bottom-up" companies, meaning engineers are expected not only to perform a task but also to figure out what task they should be performing. So, it's the engineers who propose features and then convince other engineers to join the collaboration, and then a change in the product is created. The managers just coordinate it lightly, let's say.

Marketing roles or product managers—aren't they the initiators? Is it really expected of engineers that they will be the ones coming up with executable features?

Yes, definitely. Engineers propose and explain to those product managers what is possible and what is useful. Product managers can take that into account and say: "Well, consequently, this is too expensive, we won't do that, but this is less expensive and more necessary, so we'll do this." They perform that type of role.

It's also interesting that, from what I know, there is a role called "individual contributor"—a single programmer who does everything from A to Z.

Well, individual contributor just means you don't have direct subordinates; you aren't anyone's manager.

And what does such a contributor do?

They can have various roles; they can be a software engineer. Most of the people I worked with most directly had the title of software engineer, and within software engineer, you can have specializations to a greater or lesser degree. When I started at Google in 2014, there were basically no specializations. You were hired as a software engineer and the assumption was that a software engineer must be able to do everything. Consequently, you only went to one interview, and then you could move between teams. As progress was made, it became obvious that you had to specialize a bit because computer science has expanded so much that it's very hard to work on web-dev, AI, and mobile apps all at once. So, there is a bit of that specialization now where you can, for example, specialize in machine learning and be a machine learning software engineer. So, my specialization now is machine learning software engineer. However, within that, you can still choose if you want to specialize even more—for example, only in text or only in image recognition. I prefer going in the direction of general machine learning—one that knows how to use images and text and even combine them. Well, it comes at the cost of perhaps not knowing the absolute smallest details of those very specific applications, but it's also useful for such an engineer—even if they are machine learning—to be able to work in different parts of the system, on the backend, and maybe even a bit on the frontend and the middleware, so as to bring such a solution from production and carry it through oneself, because that is the best way to coordinate it.

Those differences between working overseas and here are indeed very interesting. But let's go back to artificial intelligence and maybe continue with the differences. Namely, I heard about a phenomenon called the P(doom) score. Have you heard of it too? Could you tell us what this is about?

Yes, there's a lot of talk about it now. P(doom) is generally your personal probability that human civilization will fall as a result of artificial intelligence. However, everything I said in that sentence makes no sense, because probability is a strictly defined thing in mathematics. There is no such thing as me having a probability and you having a probability, and tomorrow I'll have a different probability. You could call it by some other value.

But why was such a P(doom) score invented at all? How is it used? What is done with it?

People who consider themselves specialists on the end of the world and artificial intelligence gather and say: "My P(doom) is 10"—meaning percent—"so 10% that the end of humanity will result from AI." Someone else says: "And my P(doom) is 90," and everyone says so, and then—what makes even less sense—they take an average of that, which makes no sense at all. But then an article is published in the press that says: "We asked experts, and experts believe there is a 40% chance of the end of the world," and people click on such articles very much. And that's probably what it mainly serves, or maybe that's what motivates the phenomenon.

Because stories about the ends of the world aren't anything new. Every so often, a new theory flies around the world about how this civilization will end, like the Mayan calendar. And currently, a new scenario talks about this artificial intelligence that somehow gets out of control, which is also, in my opinion, a bit of an absurd scenario because, if anything, we are moving away from such models—for example, evolutionary models, evolutionary algorithms—which you could somehow really strain to imagine getting out of control. Current models like ChatGPT are simply a function. Just as y=x2 is a function, so is ChatGPT a function that takes a vector of numbers, which is encoded text you write, and processes it into another vector of numbers, which is the encoded text that ChatGPT replies with. And ChatGPT can get out of control just as the function y=x⋅2 can get out of control. Those numbers won't multiply themselves; someone has to multiply them. This is additionally a deterministic function, so there is nothing there to "think up." However, people see what capabilities these models have, which they genuinely didn't have before, and they extrapolate the probability of the end of the world as a result of escaping and ending like in the movie Terminator.

Well, people are afraid of that. Yes, meaning in Europe, there are legislative initiatives, there is the AI Act, which will probably be implemented shortly in member states as well. How is it in America? Is there an attempt to regulate this area there too?

Yes, absolutely. And obviously, there is a need for it because we now have capabilities we didn't have until now, and legislation isn't keeping up. The law needs to be changed, adapted—but how to do it? It's a highly controversial topic and many people have different ideas about it.

Unfortunately, as you said, there is such dread sometimes, and that can cause over-regulation and a desire to slow down this progress altogether. Specifically, we had a lot of such open letters where people wrote to politicians and to other companies dealing with AI asking to, well, stop this development.

Elon Musk issued such an appeal, but then immediately created his own models, so that's also a bit of a strange model.

It's also strange that "to prevent bad AI, we will create our own company that will make safe AI." That is a very big trend. However, the fact is that there are various attempts to regulate AI, more similar to what is happening in Europe, which aim to limit the building of models. [7] [8]

Specifically, California has now introduced a bill that has passed through their senate for now—it hasn't been approved generally yet—which proposes something that, in my opinion, is very dangerous because it says that models above a certain size will be regulated in such a way that the creator of that model must guarantee that no one will use that model for some bad purposes—which is, obviously, impossible. Because just as when producing a keyboard, we cannot guarantee that no one will write a nasty word on that keyboard, right? Similarly, no one can guarantee that someone won't take a model and support some bad activity. So, bad activity should definitely be regulated; regulating the models themselves could lead to this industry and the development we've seen in recent years actually slowing down, and that would be dangerous in my opinion for two reasons.

First, because huge, huge benefits are coming—in medicine, for example—from these models. We can have new drugs, treat diseases that were incurable. But there is also a second danger: we have different states in this world. If some states deliberately slow down their progress, they will be behind the states that develop this technology. States that slow down AI progress will be states—as we say now—that are economically underdeveloped, and that is a big threat.

So you suggest we shouldn't hit the brakes because someone else will take over and overtake us, and they, devoid of any scruples, will use that more developed AI.

Yes, even for military applications in the worst case.

In your opinion, are there any ethical challenges related to AI development that we as humanity face?

We, as humanity, face ethical challenges. Artificial intelligence emphasizes some of these challenges, as it were, more strongly, while some are the same regardless of whether we have artificial intelligence or not. Like discrimination, for example. Discrimination… Exactly, a good example here. Perhaps I will give such an example where artificial intelligence, through the fact that people do not understand how it works, led to such institutional discrimination.

What is discrimination in general? It is when we make decisions based not on what that person has done, but on some of their characteristics over which they have no control, for example, based on that person's skin color, or gender, or height, or any arbitrary thing. This is especially glaring in the judicial system, where in the judicial system we really want to punish people for what they have done, and not because they belong to some group that statistically does something wrong, because that is… Most people believe that it is unethical, unfair. However, when it is said that way—that we are making a decision about this person based on what other similar people have done—then everyone says: “No, that is unethical, let's not do that.”

Yet, what did they do in the United States? They built an artificial intelligence model that was supposedly meant to predict the probability of recidivism, that is, to predict the probability that a given person will commit a crime. Based on this model—well, it wasn't so much used to sentence a person to prison, but for example, it could be used to decide on their extended stay in that prison or a shortened one.

This is, in my opinion, insanely unethical and unfair for the reasons I have mentioned. However, the problem of why this even occurred is that people seemingly do not understand the limits of artificial intelligence. People think that this artificial intelligence is truly able to predict whether this person will commit a crime, while of course, artificial intelligence cannot predict such a thing, because we have free will, and everyone decides for themselves whether they will commit a crime or not.

What this artificial intelligence does is simply calculate statistics—that people in a similar situation, with similar height and other characteristics, committed these crimes. So, such a lack of understanding often leads to decisions that are unethical, unfair. On the other hand, when it is said that way—that we are making a decision about this person based on what others, similar people, have done—then everyone says: “No, that is unethical, let's not do that.” However, what did they do in the States? They built an artificial intelligence model that was supposedly meant to predict the probability of recidivism, that is, to predict the probability that a given person will commit a crime. And based on this model—well, it wasn't so much used to sentence a person to prison, but for example, it could be used to decide on their extended stay in that prison or a shortened one. And this is, in my opinion, insanely unethical and unfair. For the reasons I have mentioned. However, the problem of why this even occurred? Because people seemingly do not understand the limits of artificial intelligence. People think that this artificial intelligence is truly able to predict whether this person will commit a crime, while of course, artificial intelligence cannot predict such a thing, because I have free will and everyone decides for themselves whether they will commit a crime or not. What this artificial intelligence does is simply calculate statistics—that people in a similar situation, with a similar history and other characteristics, committed these crimes. So, such a lack of understanding often leads to decisions that are unethical. [9]

And if this model was trained on statistical data, well, it contained exactly those things that started to discriminate against the people who were perhaps being evaluated by it.

Exactly, but even if the model doesn't directly have access to some data—say, regarding gender or race, sensitive data—it always has some data that is often correlated with those traits, for example, place of residence is often correlated with an ethnic group. And so on, and even if those traits aren't correlated, it is still unethical to discriminate against people on that basis.

—

Read the second part of the interview in a separate entry – click. We talk about the landscape of artificial intelligence in the USA.

—

This was a transcript of one of the episodes on our YouTube channel. If you want to hear more conversations and comments on artificial intelligence – visit the Beyond AI channel.

How do leaders of the Polish retail market talk about artificial intelligence? Check out interviews with the most interesting guests of Retail Trends 2024!

See how artificial intelligence supports blind and visually impaired people in everyday life – from navigation and object recognition to greater digital accessibility.